How I am using digital tools to do my sabbatical project

Part 1: Finding stuff to read and then reading it

This semester I am on sabbatical leave to work on the second edition of my book, Flipped Learning: A Guide for Higher Education Faculty. My sabbatical project focuses on two major additions: a collection of faculty case studies, and a completely revamped review of published research on the topic of flipped instruction. When I first planned the project, I figured the case studies would be seriously time-consuming because they involve summarizing several rounds of interview questions given to 20 different faculty, and I thought the research review would be something easy that I could do in the background. But it turns out that the opposite has been the case.

When I wrote the first edition in 2016, the sum total of all research on flipped learning was contained in about 250 papers, a number small enough that a comprehensive review of that research could be done simply by reading all of it. Today, however, that number is an order of magnitude greater. Not only has the quantity of research grown, the tools for reviewing it have greatly evolved as well. So I learned very quickly when I started last month that I needed to figure out a whole new workflow for doing a research review.

This article is part 1 of a two-part series on how I am approaching this research review and the tools and workflows that I’m using to do it. I want to remind everyone that intentionality in academic life and work is not about tools, apps, and gadgets but rather about taking small steps within coherent systems. But since I recently posted about tools such as Obsidian and Todoist, I thought this would be a good opportunity to show how those can be put to use. And I’m not at all sure I have this completely optimized, so I’m putting this out there for you to give me ideas on how to improve my workflow.

What I am doing, and what I am not doing

The first thing to understand is that my book is not what I would consider a “scholarly volume” — a thick tome intended for experts on the subject. Instead, it is a practical book about teaching, written for faculty in the classroom, focusing more on blueprints rather than theory or deep analysis. So when I say “research review”, this is not the kind of review that you would find in something like a comprehensive scoping review or meta-analysis. I am not attempting to be fully comprehensive and I am not following the usual practices for comprehensive reviews. I’m simply taking the point of view of what an average reader would want: To look around at what the research says about flipped learning, and interpret what it means on a practical level — something I could use in a class tomorrow.

When you look at it from that point of view, there are at least four distinct actions that I need to perform in this review:

Finding research papers that have something interesting and useful to say about flipped learning;

Reading those papers and taking notes that distill the main ideas and takeaways for my readers;

Curating those notes and discovering connections between them to uncover patterns in the research; and

Keeping track of what I’ve read. what I need to read eventually, and what I need to read next.

Early on in the project (meaning, four weeks ago), I discovered that friction on any one of these points grinds the entire review process almost to a halt. When I did the research review for the first edition, I did not have a reliable system for managing what I was doing, nor did I really need one. But I soon found out when I began work this time that I needed to have a coherent system within which I could make small daily steps. Otherwise I would end up wasting time, a scarce resource as I need to complete this project by the end of 2025.

Discovery: Scite.ai to the rescue

The general question I am addressing is: What does published research say about flipped learning? This question is ridiculously broad. To get my arms around it, I broke it up into five more targeted questions:

What is the impact of flipped instruction on student academic outcomes?

What is the impact of flipped instruction on the overall student experience apart from academic outcomes (engagement, belonging, metacognitive growth, etc.)?

How do instructors experience flipped learning, and what best practices have emerged?

What is the impact of emerging technologies (artificial intelligence, virtual reality, etc.) on flipped instruction?

What impact did the Covid-19 pandemic have on flipped instruction?

Implicit in these questions is “What does the research say about all this?” So, the first step is to find “the research”.

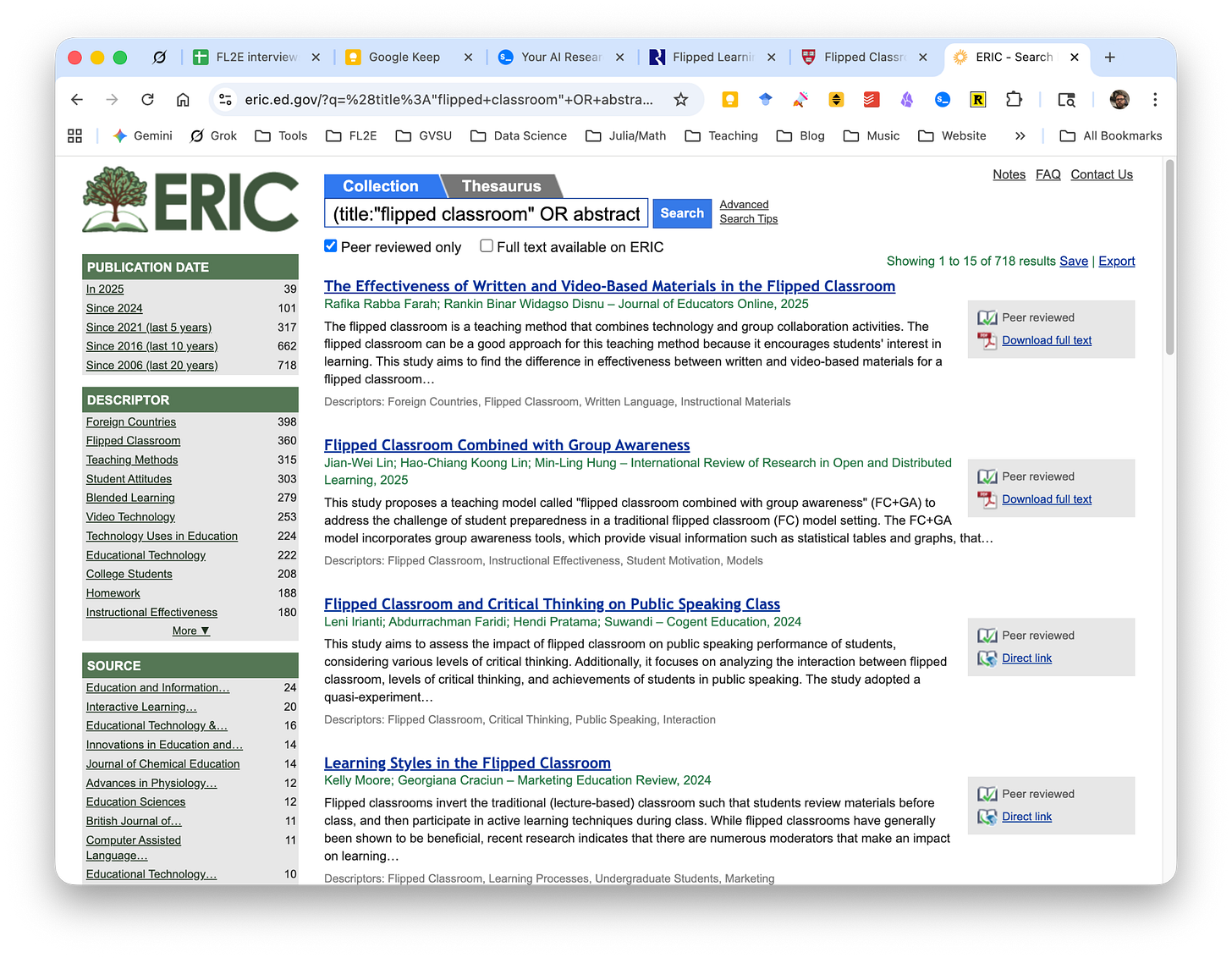

The typical way to do this is to go to an academic database like JSTOR, SCOPUS, or the ERIC database and put in some rather complicated queries for what you’re looking for. And what typically happens is that you get hundreds, if not thousands of papers to sift through, usually given in no particular order:

This is how I started the research review process last time, 10 years ago, and it’s how I began this time too. But when I started seeing the sheer number of papers to sift through, I decided that I had neither the time nor the inclination to read through it all, nor to craft complicated custom queries to get what I wanted (which may or may not actually get me what I wanted).

What I really wanted, was a smart graduate student, to go out and find this stuff for me in an intelligent way, and bring back a small number of the best results for me to review. Well, I don’t have graduate assistants. But I did discover Scite.ai which has turned out to be perhaps the next best thing.

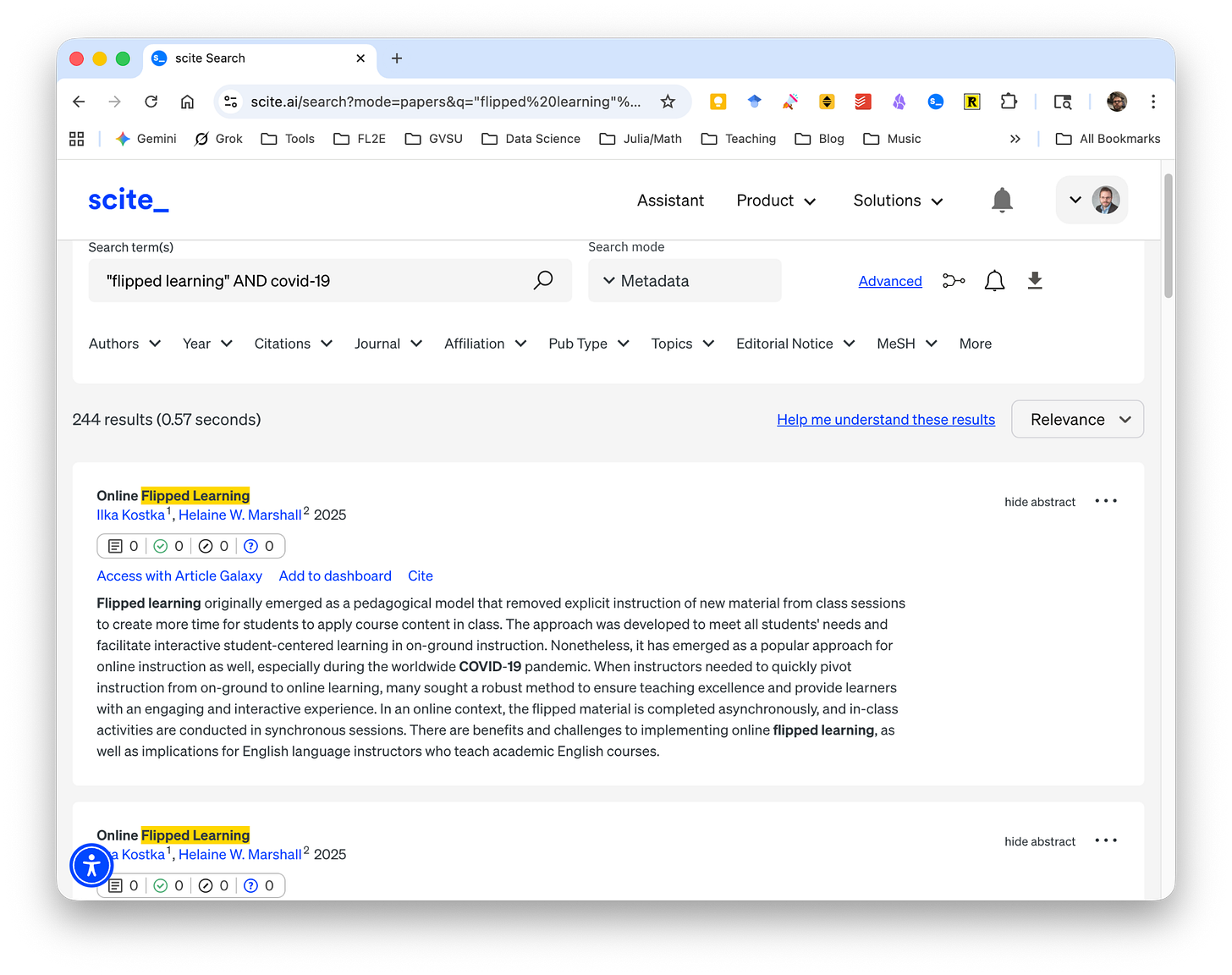

Scite.ai is an artificial intelligence tool that is like many others where you can ask it questions and it gives you answers. But instead of LLM-generated text, it gives you detailed reviews and citations of published research articles. The user interface can be switched between Assistant mode, Search mode, and Table mode. Search mode is like a typical academic database search:

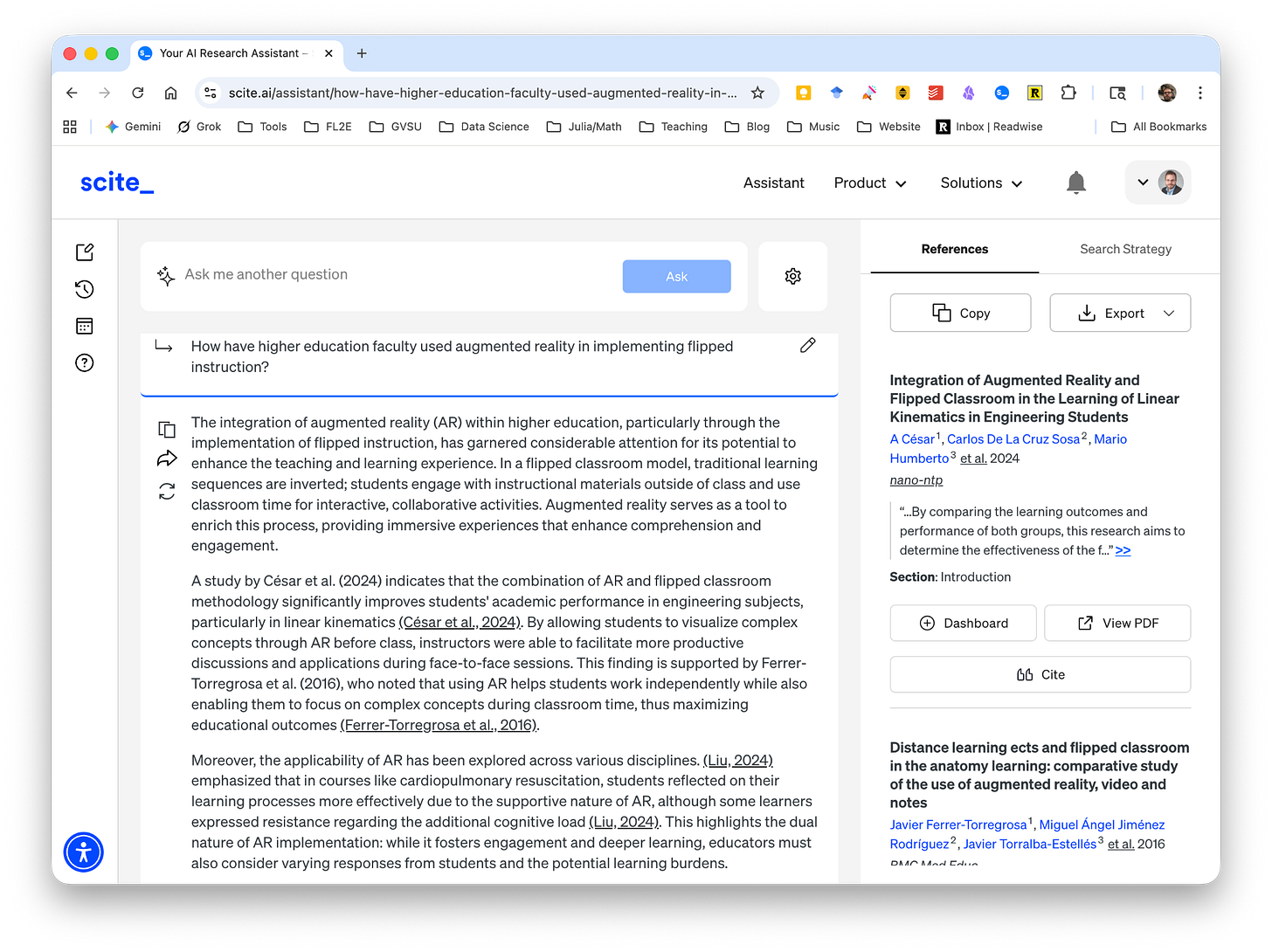

But the special sauce in Scite.ai is in Assistant or Table modes. Here, you just ask a question, and it finds the research for you. Here it is in Assistant mode, where I am asking How have higher education faculty used augmented reality in implementing flipped instruction? And as you can see, it generates a search of the literature, summarizes the results, and puts links to the original sources in the sidebar along with stats about those sources.

The same question asked in Table mode produces a list of papers, with references, and summarizes them next to the reference. You can add columns for research methods, population, and more.

The way I’m using Scite.ai is to ask targeted sub-questions related to my five main research questions, to discover papers that seem to be central or seminal. For example: What are the most frequently cited peer-reviewed articles focusing on the effects of flipped instruction on student self-regulated learning? The results in Assistant mode look like this:

As with all AI tools, you have to exercise some caution in the results. I have yet to encounter a hallucination with Scite.ai (you can click into the results to verify the papers are real) but clearly, in this case, it is playing loose with my “most frequently cited” criterion — the top result is only cited once! However, the next one is cited 258 times, which in this field would be considered a lot of citations. It’s therefore probably an actually-influential paper, and therefore a good starting point for my own review of this sub-question1.

I have a whole collection of these targeted sub-questions that I keep in my project notes in Obsidian (more on those in the next post). Each one gets a Scite.ai search like this. I copy the summary text and paste it into the note for that sub-question for reference; then pick through the sources that seem to be most central/influential/seminal, and go look them up. (It’s possible to look them up directly within Scite.ai, but there are often paywall issues, see below.) Those papers go into a queue for reading, and as I read those papers I add any others from the reference section that also seem important.

In other words, Scite.ai points me to appropriate starting points for finding papers that have something important or useful to say, and I take it from there. I find this to be a much smarter strategy than the typical database-surfing, and it’s AI used the way it ought to be used — as a kind of powered exoskeleton around my brain.

Interlude: Academic publishing sucks

No offense to my wonderful partners at Routledge who publish my books, but academic publishing on the research side of things is a royal pain.

Some of the papers that I discover and then go look up — so far I’d estimate about half of them — are freely available as PDFs. The other half are hidden behind a rat’s nest of paywalls. There are usually ways around these if you are employed at a university. For example, the paywalls sometimes disappear when I log in to my campus network using a VPN. Sometimes they don’t; but then I can usually go to my university’s library page and log into our institutional JSTOR account and get access. Except for the times when this doesn’t work. I could use Interlibrary Loan, but that takes time (which remember is scarce). Sometimes, when the usual methods fail, I can somehow get a janky-and-possibly-illegal copy of the PDF online, and often it’s something like a manuscript rather than the final product, so it’s hard to trust. And sometimes, none of this works, and the website and Scite.ai are just sitting there placidly telling me that I can purchase a copy of that paper for the low, low price of $29.95.

Look, I understand that the primary function of a publishing company is the same as any company: To make money. These are not charitable organizations, or patrons of the sciences. Most of their money is made via subscriptions to journals. So I get it: When making a paper freely available causes you not to sell more subscriptions, then you don’t make them freely available. Or, you ask for an “Article Publishing Charge” — a one-time fee paid by the authors (or their institutions or granting agencies) to make the article open-access, at a high enough amount to recoup the potential loss of subscription revenue. This charge is typically in the thousands of dollars.

I have no problem with capitalism in general. But this practice of paywalling research articles, some of which are 10 years old or more and many of which result from research that was funded with my taxes, has gone too far and it’s been the primary headache of this project. I would simply propose that any research paper that is older than 5 years should be made freely available as an accessible PDF on the publisher website.

Now back to our regularly scheduled blog post.

Doing the reading: Filtering, ToDoist, and Zotero

So Scite.ai is my primary means of bootstrapping the research reading process, and the discovery process continues by recursively going through the bibliographies of the papers I find — being picky the entire time because I am looking for a moderately small body of highly influential research to review, rather than trying to consume it all.

When I encounter such a paper, I (attempt to) access it, then read the abstract and the discussion section to see if it’s relevant. Sometimes the title catches my attention but it turns out to be a dud2. If it’s a non-dud, though, I do three things.

First, I add a task to read the paper into ToDoist, which if you are new around here, is basically my life’s operating system. I have ToDoist projects set up for each of the five primary research questions (e.g. “Conduct research review on emerging technologies”) and each paper is a task3. This allows me to put individual papers on the radar screen for the day’s work, or to complete within the week, and so on.

Second, I have a Google Spreadsheet set up that I use to keep track of these papers:

The reason I keep the spreadsheet in addition to the ToDoist projects is sort of embarrassing: I was forgetting which papers I had read. I’d check off the ToDoist task for a paper, let’s say Hung Yeh 2023, after I read it. Then, time would pass, and I would encounter Hung Yeh 2023 as a reference in some other paper and think, Wow this sounds like a useful paper, I should download it and read it. Then I’d go through this process I am now describing only to find out I’d already read it. This was starting to happen a lot, sadly, so I built the spreadsheet as a sort of database to help me track what I’d completed (since completed tasks in ToDoist are not visible by default).

Third, and most importantly, once I decide to read a paper, I download it and import it into my research paper management tool of choice: Zotero.

I’ve been using Zotero for many years4 and I really like how it “just works”. When you find a PDF of an article, you simply drag and drop it into the software and it magically ingests it into a library — that is synced to the cloud so you can access it across devices — along with a ton of metadata about the article. For the research review, I have five “collections” (like sub-libraries) set up for each of five main focus questions. As I move through the project, I am tackling one major sub-question at a time and the subcollections keep me focused.

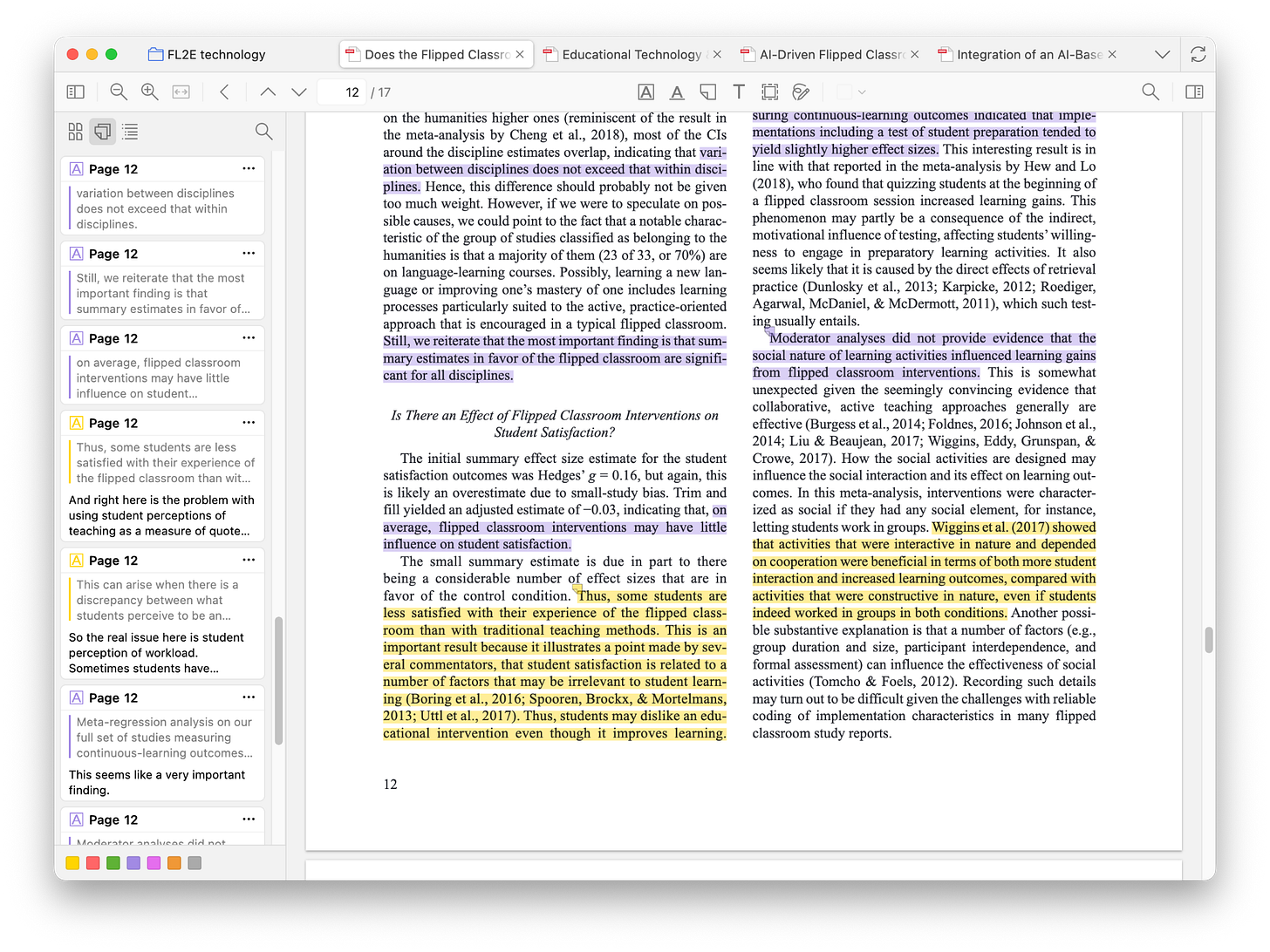

The reading of the papers takes place within Zotero. In the PDF, it’s easy to highlight and add notes to a paper:

I have a color-coding system that keeps the annotations categorized, which comes in very handy in the next stage when I import these notes into Obsidian. Here, yellow means “interesting point” and purple means “main findings”.

Those annotations live in Zotero with the paper as just another set of metadata. The original PDF is there too and accessible if I want to share a clean copy with someone.

For next time

In summary so far:

Scite.ai is my go-to tool for discovering papers to read, because it allows me to just ask a good question and get pointed to important, relevant research — rather than having to outwit a database using search queries. Once I discover a few central papers, I can use those papers’ references to keep iterating.

Zotero is where the papers actually get read, along with notes and annotations.

ToDoist and Google Sheets help me organize these paper-reading tasks into coherent next actions so that I will be aware of what I have already read, what I need to read eventually, and what I need to read next.

But this is only the front end of the process. The real work is in taking those notes, annotations, and insights from reading the research and getting them into a system where it will be easy to see the connections between them as well as the overall picture, and eventually turn those into a manuscript I send to the publisher in a few months. This is where Obsidian really shines, and there’s so much to this that I’ll need another post in a couple of weeks to do it justice.

Indeed, one of the papers I ended up finding was a bibliometric analysis that confirmed the van Vliet et al. 2015 paper in the lower-right of this image was one of the top-10 most-cited papers on flipped learning across all subtopics.

For example, many papers that had “Covid-19” in the title or abstract, turned out to have almost nothing to do with the actual pandemic — the authors were just publishing in the time frame from 2020 to 2022 and stapled “Covid-19” into the title or abstract I guess as a hook, to make it seem incredibly relevant and timely. You have to actually look at the paper to find the truth, it turns out.

You might consider reading a paper to be more of a project than a task, since this is a non-trivial thing to do, and often it requires multiple steps like read the abstract, then read the discussion, then read the methods, etc. I take a much more lean approach to reading these papers that generally concludes itself in a single 30- to 45-minute sitting, so for me these are actual tasks.

I used to be a Mendeley guy but switched when Elsevier purchased Mendeley in 2013.

Excellent!!