Controlling the controllables

Reframing and reaffirming the core principles of Intentional Academia for 2025

Two years ago, I posted the first article at this newsletter. I explained how I came to be interested in “productivity”1 from an academic standpoint, and then gave four statements about “productivity” as an academic which were meant to serve as the ground truths for the other 25 articles I’ve posted here since then.

The opening sentence of that article – “Let’s start with gratitude” – still works. Since then, this newsletter has somehow acquired over 600 subscribers, including several new paid subscribers, and I am thankful for all of you, and for those who are reading but not (yet!) subscribed. This year I am committing to producing much more content here, starting today.

I spent part of the holiday break mapping out what I’m going to write about, and when. As I did, the big picture came into focus. It became clear that the first thing to do is reaffirm the core principles of intentional academia2. I originally laid these out in that article from two years ago, as four basic ground truths. Over the next three weeks, I’m going to update these, reframed as three foundational ideas that are essential for any person in academia who wants to build the kind of life and career they can be truly happy and proud about.

Not everyone agrees that these principles are realistic or even valid. In fact I’ve gotten quite a bit of pushback from some on these. I don’t expect full agreement with everything I say3 but if you are going to read this newsletter, you deserve to have the axioms clearly stated. If you don’t agree with or like those axioms, then at least you know what you are in for.

Control the controllables

The first fundamental idea of an intentional approach to academia is: You must be aware of what aspects of your work and your life are within your control and what is not within your control. And, to the extent that something is within your control, you must exert control over it.

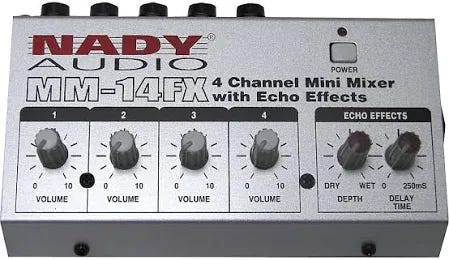

The word “control” can seem very aggressive. But what I have in mind is a more like the image at the top of the article, which shows a recording engineer at the recording console in a music studio. There are a lot of dials and sliders and so forth at one of these consoles. Here’s a close-up of one that would be considered “medium-sized”:

The ports at the top are where instruments and microphones plug in, and each thing that’s plugged in gets a vertical slice of the board with its own set of knobs, buttons, and a slider. Each one of the doodads on this board does something. The sliders at the bottom handle the volume. The knobs and buttons control the bass, treble, and midrange frequencies; whether the output signal is on the left or right; whether the input is muted; and so on. And there are other knobs and sliders besides those, that do things to the entire range of sound coming out of the board.

The main job of the recording engineer is to use this console to take the raw sounds coming into the board, and “mix” them so that what comes out is aesthetically pleasing and makes the musicians (and the record company, or the audience) happy. It’s called a “mix” because that’s what it is: A mixture of dozens of choices about controlling what’s coming in to produce something awesome coming out.

And that’s the sense in which I mean “control the controllables”. You have all these inputs coming in that are just raw sound, perhaps even noise. Your job is to be the recording engineer of your own life: Get the inputs plugged into the right places, and use a knob or a slider that can help you take all that raw input and turn it into music.

A word about responsibility

Sometimes people stop me at this point and ask: What do you mean, “my job”? Are you trying to tell me I am not working enough as it is? Who do you think you are, placing more work on me like this?

Nobody is “placing work on” anybody. This is work that is already there, regardless of who you are or who else is around you, and nobody can do it for you or take it off your plate. So the idea of controlling the controllables goes back to the original formulation in my very first post: The statement that you are responsible for your career.

This concept really makes people mad sometimes, with one specific objection being that it puts unfair amounts of work on those who are disadvantaged by our current system of higher education, and until there are big systemic changes, I should not be telling people what to do. Here’s a recent example, if you don’t believe me.

I will have a lot more to say about that specific objection in two weeks. For now, I’ll just say: I don’t deny that this responsibility is real work and that it falls on some more heavily than others — which is unfair. But it’s still work that has to be done, and there is nobody around to do it but you. There is no other person, or system or organization riding to the rescue to take it off your plate. You either accept the responsibility or cede control of your life to that very system.

What is controllable?

Back to the main post: Controlling the controllables starts with identifying what’s under your control and what isn’t.

Some people have more control than others. For example, I am a tenured full professor. So, I have a ridiculous amount of autonomy. I can say “yes” or “no” to just about anything — teaching, scholarship, service work as well as stuff outside work — at will, if it’s not a core job duty in my contract. I’m never going to fail to do those core duties, and will never shift my work onto someone else just because I don’t feel like doing it. But I have lots of choice, and the primary guiding principle for my choices is whether or not the thing serves my near- and long-term goals and values.

Others don’t have so much autonomy. You might not be able to just say no to a work request, and doing so with the reasoning of This doesn’t align with my core values may be true but also a fast track to unemployment. You may not be able to, as I often do, cut unnecessary topics from a course in order to focus on essentials and give time for feedback.

But I will say: As limited as your sphere of control may be, it’s never zero. Your professional “mixing console” may look more like this:

But you are never simply at the mercy of your inputs — unless you choose to be. The question is simply, what “knobs” and “sliders” are available to you?

I can’t answer that question for you. But many of the controllables that are available to everyone, include:

You can control whether you employ simple practical techniques for managing ideas. For example, there is nothing preventing any person from using a little memo pad notebook — here’s a 5-pack for $7.19 — and a pencil to capture ideas and potentially actionable items as they occur to you, rather than saying you’re too busy/too tired to do so and just resolve to “remember” them for later4. There is nothing preventing you from taking 15 minutes a day5 to go through the captured stuff and clarify what it means to you. Much more on this in the next article.

You can control your awareness of your core values and principles. I went into this in some detail in recent articles including the one just linked. There is nothing preventing you from sitting down, either in several short sessions or one big one, and writing out what I referred to as a Life Plan and Horizons 4 and 5. You may not be able to move in a professional direction, at the moment, that fits with those values. But someday you might; and when that time comes, you had better be well acquainted with yourself or else you will miss an opportunity of (quite literally) a lifetime.

You can control your awareness about whether something that seems out of your control, really is. This one is a little harder. Sometimes we think something is out of our control but this ends up just being an assumption, and in fact you do have control over it. Suppose you are asked to represent your department at some function that takes place on a Saturday morning, but your child has a soccer game then and it’s important to you and your child that you are present there. Don’t simply assume that you’ll get dinged on your tenure portfolio or contract renewal if you beg off. Ask about it: I’m happy to help, but Alice has a soccer game then. Is there some other way I can contribute? It’s possible that your chair is such a jerk that they would downgrade you for this6; it’s more likely that the chair will view this as the act of a sane, balanced person and in fact they have probably been in the same position.

You might be surprised just how many knobs and sliders you actually have.

How to control them?

This is another question I can’t answer for everyone, because everyone’s mixing board is different. But in my experience, effective acts of control have some characteristics in common:

Control takes place from a place of humility and service. It’s easy to get the impression that “exerting control” means acting out of pure self-interest. And that’s not totally wrong. But what keeps control from being pure selfishness, is that the more mature you get, the more your self-interest changes: Other people’s needs become a core part of your own needs. Some people have defined “love” in this way. So the main question still becomes whether something aligns with your core values; but service to others becomes one of those core values in mature people, eventually. (The skilled recording engineer isn’t trying to make music that they, alone, enjoy.)

Control is exerted decisively and without apologies. A skilled recording engineer knows that a twist of a knob may not work in terms of making the music sound better. But they don’t dither about it or ask for permission to make the choice. They just do it, maybe explain what they’re doing, and then take ownership of the results (including changing things back if it didn’t work), because they’re in charge of that job. In the example of the Saturday soccer game, the hypothetical response is just a statement of fact: My kid has a soccer game then with the implication, And I’m going to it. Not, “Oh geez, sorry, could I pretty please be an engaged parent just this one time?” The latter is more appropriate for an indentured servant or a groveling character in a Dickens novel than a highly trained professional. You’re responsible for your career, so don’t be afraid to take charge.

Control takes place within the context of a larger system. When operating a mixing board, it’s not just one knob that does everything but the blend of all of them. There’ll be much more to say about this next week, and my entire GTD series is really about this. Actions like these always exist within a larger context of managing information and commitments, so there should be a coherent system in place.

So in order to be truly intentional about life and work in academia, you have to control the controllables — know what these are (and don’t underestimate how many there are) and exert control over them with confidence. As I mentioned, next week we’ll get into how that works within the context of a larger system.

Small win

Here is something simple that you can do: If you are asked to serve on a project team (or committee, task force, or something else relatively project-like) — especially if you are simply added to the team without being asked first — don’t just say “yes”. First, ask a few counter-questions to the organizer:

What are the time requirements, per-week and overall?

How often do you plan to meet, and during what day/time slots?

What expectations are there for me in terms of workload, including communication?

What is the time frame for ending the project?

Then say that you'll consider being on the project one you have that info.

It may sound snarky, but in fact you need this information. (This stuff really ought to provide it up front, because that’s Project Management 101, but it rarely seems to happen.) If the organizer doesn’t know, or doesn’t want to commit, then you’re within your rights to withhold a “yes” until they do. You might still feel pressured to say “yes”; and you can still do that if you feel like you should, but asking these questions at least makes the organizer stop and think about things, and establishes you as something other than a pushover. And again, you do actually need this information regardless.

Etc.

Shameless self-cross-promotion: This year I’ll be working on the second edition of my 2016 book Flipped Learning: A Guide for Higher Education Faculty. If you or someone you know works as an instructor in higher education at any level and uses some form of flipped learning, I am soliciting interviewees for new chapters in the book featuring real-life use cases. Here is a form to indicate interest (with a working definition of “flipped learning”).

Music: I learned yesterday that legendary soul band Booker T. & the M.G.s did an entire album of instrumental covers of Beatles songs. It’s by far the weirdest album I’ve heard in the Stax catalog. Here is their medley of “Because” and “You Never Give Me Your Money”. I can only imagine the amount of psychoactive substances that were involved here.

This word, “productivity”, is in quotes for reasons I explained in that article: The term “productivity” often is used to connote simply “doing more” or even “doing more with less”. That’s not how I mean it; for me the term means, focusing on producing things that are of value to you in your career and life so that you can be fully present and engaged with the stuff that matters. But, “productivity” is a recognizable handle.

Both the blog with capital “I” and “A”, and the general concept with lower-case “i” and “a”.

I’ve raised three kids, so I’m used to it.

I put that word “remember” in quotes because we all know we won’t remember it later; and trying to do so, rather than writing them down in a notebook, contributes to the very mental overload that makes people so tired and busy.

I promise you, with every fiber of my being, that you can find 15 minutes a day to do this, and get it done in 15 minutes.

If this is the case, then it’s useful to know this information; and if it were me, I’d be looking for the exits.