How and why I use Obsidian

Tools aren't the main thing, but they're an important thing

A big mistake many people make when trying to be more intentional about work and life is to fixate on tools — apps, gadgets, websites, you name it. Just look at all the articles whose title is something like “I switched from [insert name of app here] to [insert name of another app here] and I’m never going back”. Or sometimes it ends “...and I’m really disappointed”. Being intentional isn’t about tools: It’s about shaping your behavior.

But at the same time, tools are important: “The tool shapes the hand”, and the tools you use (analog or digital) can make behavior change either easier or harder. This month at Intentional Academia, I’m going to focus on two apps that are part of my everyday toolbox and which I’ve mentioned here many times before: Obsidian and ToDoist1. These are digital tools that don’t do everything for me, and never will, but make it a lot easier for me to do the boring work of taking small steps taken within coherent systems.

What is Obsidian?

Obsidian is an app for taking notes, in the same vein as many other notes apps like Apple Notes, Google Keep, Evernote, or Bear. What makes it different from the others (all of which I have used before, and which are very good) is that Obsidian is just a wrapper around a folder of Markdown files.

There’s a lot to unpack in that statement and why it matters. Let’s start with Markdown.

Markdown is a “language” for formatting plain text files. Here is what some of the basic syntax looks like in plain text on the left, and on the right it shows what it looks like when rendered using a previewer. Notice how the plain-text formatting on the left actually looks like the finished-product format on the right2:

Markdown is not an app — it’s a language, a cousin to HTML and other “markup” languages. Files written in Markdown are just plain text files with a .md extension. There is not just one “Markdown app”. In fact there’s a dizzying number of apps that use Markdown, and it’s built into some other applications too, like the comment systems on Reddit and GitHub. Google Docs now offers Markdown syntax highlighting and seamless copy/paste integration with Markdown, and text editors like VSCode have tons of Markdown plugins and functionality.

Markdown was invented in 2004, and I discovered it around 2015 (way before Obsidian existed) and quickly became a convert. It’s simple, free, lightweight, flexible, and future-proof. (Word processing and fancy note-taking apps come and go, but plain text files are forever.) Soon after learning Markdown, I began to create all my course materials using Markdown whenever possible. I even wrote my first book using Markdown. I still take a Markdown-first approach to everything, from writing blog posts to creating syllabi and everything in between.

Back to Obsidian: Every note in Obsidian is a Markdown file — a plain text file — stored in a folder on your computer. That folder is called a vault. Obsidian lives in that folder as code that accesses the notes, displays them, lets you edit them, and provides a bunch of useful functionality. For example, there is a nice search feature for your notes, formatting options for math notation and code, and fun stuff like the ability to turn a note into a slide deck.

Most of the features aside from search and formatting use plugins which are optional add-ons to the core system. There are “core plugins” that come with Obsidian but also a huge and growing library of plugins contributed by the user community that run the gamut from improved search engines to AI chat tools to integrations with other tools like ToDoist or Zotero,. There are also hundreds of user-created themes that change the visual aesthetics.

The most significant feature of Obsidian is backlinking. You can link one note to another by entering the title of the target note inside double-brackets [[ ]]. In the source note, the title becomes a clickable link that jumps directly to the target. Backlinking turns a vault of notes into a wiki. Obsidian allows you also to search for backlinks that could exist but don’t, and insert links where appropriate. So, for example, if I have a note titled “Intentional Academia” in my vault, I can check the entire vault for any note containing the text “Intentional Academia” and in one click turn all those other references into hyperlinks that jump to the “Intentional Academia” note.

Backlinking is incredibly powerful. It turns a vault into something more than just a folder with a bunch of files in it: It becomes a network of interconnected ideas. This is why Obsidian is sometimes referred to as a “second brain”. You can even visualize your network using a graph view. For example here is the graph of all the notes in my vault that are tagged #writing. Each dot in the network is a note/file, and each edge is a link between the files. Clicking on a vertex opens the note.

Despite all this fancy functionality, the thing I like the most about Obsidian is that the notes are not part of the app3. They are just Markdown files, with a separate existence from the app that works with them. If Obsidian ceased to exist, or had a bug that made it unusable, all my notes are still there in a folder on my computer. I can open, edit, copy, paste, delete, etc. them just like I can with any other file, using a text editor and my computer’s built-in file management. This is in stark contrast to proprietary note taking systems like OneNote or Evernote, where the notes are made inside the app and are only usable via the app, and if you wanted to move your data to another system you would have to deal with complex and buggy export/import tools.

Obsidian itself is free. But you can sync your information across different devices, the best way being to pay an annual subscription for their native sync service which is $48 per year — worth it as is, but there is also a 40% educational discount available which makes it even more of a no-brainer4.

How I use Obsidian

I’m obviously a big fan of Obsidian. But I do not use it for everything. I don’t use Obsidian for:

Quick capture of passing thoughts. Google Keep, or a little notebook, in my opinion is a better tool for this.

Task management. Although task management plugins for Obsidian exist, I find ToDoist to be superior to all of them, and if I really need to work with tasks in Obsidian I use this ToDoist integration plugin.

Calendar. Again there are calendar integrations for Obsidian but I prefer to just use Google Calendar because it’s simpler.

File storage. It’s possible to embed some files, particularly PDFs, in Obsidian notes and even highlight and annotate those embedded files within the Obsidian note. But I prefer not to use Obsidian for the actual storage of files, because it gets complicated (I’m storing a file inside another stored file…?) and anyway this is what Google Drive and OneDrive are for.

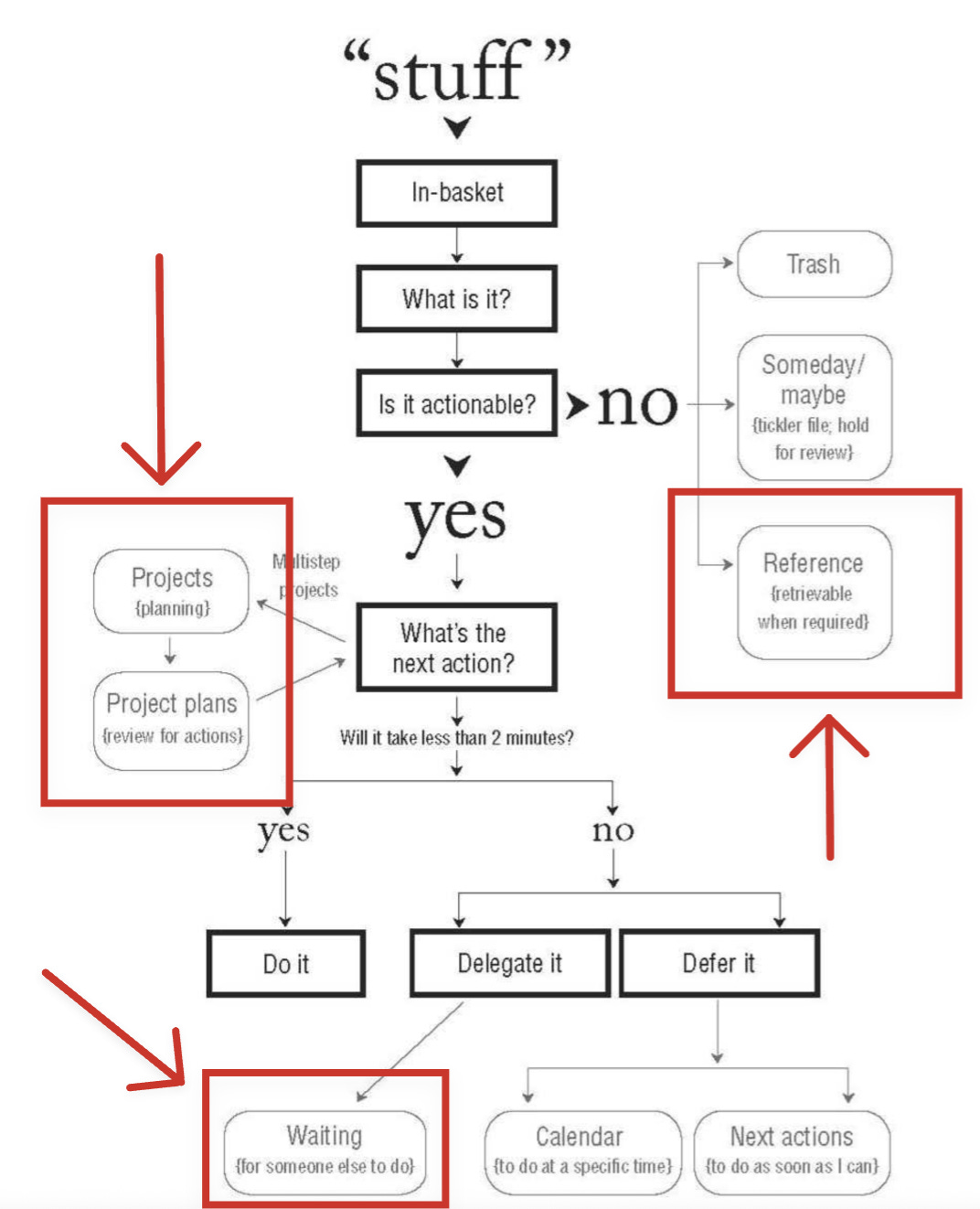

This may make it sound like I don’t use Obsidian for much, but that’s far from the case. Obsidian is my preferred tool for these parts of the GTD Clarify flowchart:

Reference material: If I have “stuff” that is not actionable but is something that I might want to refer to later (that is not a file unto itself, or an email) I will usually create an Obsidian note, dump that info into the note, and tag it with the name of the project it belongs to (if there is one), then backlink to any related notes.

Projects: In GTD language a “project” is any desired outcome that requires more than one action step and that I intend to complete within 12 months. Most of us have between 10 and 50 active projects underway at any given time. For many of these, I create a single note that serves as the “home page” for the project, listing things like the project parameters (who is involved, what are the outcomes, what are the key dates, etc.) and other pertinent information. The project home page is a combination of project charter, statement of work, and other project management basic documentation. Other stuff related the project might live in different notes. For example, if I’m giving a keynote address, there will be a home page for the event in one note and the draft of the script in another note. Then I link the secondary notes back to the homepage with a backlink. So all information related to the project is no more than a couple of clicks away.

My Waiting For list is an Obsidian note. I do not use Obsidian for Next Actions or Someday/Maybe because unlike Waiting For, those lists consist of tasks, and ToDoist is where my tasks live.

I also use Obsidian for:

Longer-form passing thoughts that are too big for Google Keep. These often turn into blog posts, so I tag them with the name of the blog I might publish them at, and search for them later when I need to write something.

All my GTD higher horizons documents — Life Plan, Horizon 4, and Horizon 3 — as well as records from my Quarterly Reviews and Weekly Reviews.

Notes from my Kindle and web content reading. Obsidian integrates with the read-later service Readwise and this has been a game-changer for me. If I am reading an article on the web or a book on my Kindle and make a highlight, the highlight is synced with Readwise’s online service and then the Readwise plugin will pull all the information about the article along with my highlights, into my vault, with links back to the original. All I have to do is highlight the original with my finger or mouse.

My daily journal. I used to use a paper notebook for journaling, then a smattering of apps like DayOne, but finally settled on using Obsidian along with the Periodic Notes plugin.

Other more creative uses of Obsidian are definitely possible. Recently I made a new vault entirely focused on my music pursuits, with notes for practice logs, links to articles, information on people and venues, setlists, information on my gear, and more, all linked together. And a couple of years ago I created a vault for my discrete math courses that serves as a course wiki, which has been put online using the Obsidian Publish service which Obsidian offers for an annual fee. (fn: There is a 40% educational discount for Obsidian Publish, and I highly recommend it.)

My Obsidian setup

Obsidian is flexible with how you organize it. Remember it is just a folder of Markdown files that live on your computer. You could choose to have no organization at all, just dumping the files into one big container and then linking them. Some users add tags to their files and organize around a coherent tagging structure. I’m a little old school, and I like organizing files by subfolders. I have five main folders labeled:

0 - Inbox

1 - Projects

2 - Areas

3 - Resources

4 - Archive

Subfolders 1–4 follow the PARA system that I have mentioned once before. There are secondary folders that live outside these five. One is Journal which contains all my journaling entries. Assets is where I put attachments like images or audio files5. Notes from Readwise are put by default into a Readwise folder. And so on; and all this can be changed and tweaked in Obsidian’s settings.

What is supposed to happen in my system, is that each week at the Weekly Review, I go through the Inbox folder and Clarify each note and put it in the folder where it belongs. This is what’s supposed to happen. But in reality, I have not really used folders that much but instead rely on tags, backlinks, and search to get to the files I want, and I have not actually processed the Inbox folder in some time because I haven’t really needed to. Unlike email, where each inbox item is equally likely to be a massive project or a nothing-burger, and therefore I need to Clarify each thing to know what it means, notes are in Obsidian in the first place because they’ve already been Clarified and this is where they belong. I just need to be able to find them if needed, and folders are helpful for this but in my view not necessary.

Who this tool is for and why you might use it

The life of the mind is all about having ideas and playing them off of each other. Having a way to capture and process your thoughts and, especially, discovering the synergy between thoughts you didn’t necessarily realize were related, is where a lot of our best work comes from. This is why you might choose to use a notes app in the first place. They make it easier for many people to capture passing thoughts for later consideration, search them up when needed, and discover the connections that lead to more ideas. Paper notebooks can serve in this capacity but if you’re like me, I have my phone almost constantly with me but it can be annoying or impractical to carry around a notebook.

Obsidian might be a good choice for you, compared to other notes apps, if, like me, you:

Have at least a passing familiarity with Markdown or are willing to learn

Want notes that are simple plain text and are willing to sacrifice some bells and whistles

Don’t want to become too depending on any particular notes app, but instead have full control over how to work with your notes

Want not only to store and search notes, but link them and discover connections

Don’t want to pay for your notes, but don’t mind paying for syncing or publishing

If you’re going to use digital tools at all, it’s crucial to keep them simple, lightweight, and trustworthy. Obsidian ticks those boxes for me and maybe for you as well.

Etc.

Since we’re talking Obsidian, I should mention my must-have community plugins: Dataview, Emoji Shortcodes, Git, Kanban, Natural Language Dates, Paste URL Into Selection, Periodic Notes, Readwise, ToDoist Sync, QuickAdd, and Templater. That’s basically a complete list of plugins I use because I want to keep the system minimal and not get too far away from the “just a wrapper around Markdown files” philosophy.

For Obsidian themes, I’m a big fan of the Minimal theme but Flexoki is what I’m using currently.

Music: Pino Palladino, who is on my Mt. Rushmore of bassists, is back with another collaboration with guitarist Blake Mills and drummer Chris Dave. This one gives some early Peter Gabriel vibes.

Both this post and the next one are my own personal reviews and not official endorsements from either Obsidian or ToDoist — everything you read here is totally honest and unbiased. Although, if either company wants to give me a sweet paid endorsement, hit me up.

I used the free online Markdown editor Dillinger for this example. There’s much more on the syntax of Markdown at the canonical Markdown Guide. Although note that not every Markdown editor does everything in that guide, for example Dillinger doesn’t know how to do LaTeX math syntax. For more features, try HackMD.

Obsidian is cross-platform, available on Mac, Windows, Linux, Android, and iOS — but no browser-only implementation for now.

There are a variety of other ways to sync your data, for example using GitHub. But Obsidian Sync seems faster and less error prone, and $30 a year seems like a reasonable price to support really good software.

Although Obsidian notes are just plaintext Markdown files, you can embed media into them by simply dragging and dropping the media into the Obsidian file. Behind the scenes, Obsidian imports the media into your vault (this is what the Assets folder is for) and then creates a link from the note to the media using standard Markdown media linking syntax. One of the strengths of Obsidian is that the user doesn’t have to think about any of the coding, they just drag and drop.

Woah, this is similar in structure to my recent post https://onthemezzanine.substack.com/p/on-a-little-electronic-help-pt2 . I’ve been inspired and borrowed a lot of ideas from Robert Talbert over the years, including some I share in that post, so it’s crazy to think that I may have inspired him back