A “knowledge worker” is someone with a high level of specific domain knowledge who applies that knowledge to develop products and services. If you’re a faculty member, then you are a knowledge worker. But somehow we seem different from private-sector knowledge workers like engineers, designers, or technical writers. We’re trained as faculty to expose ourselves to ideas more, and we have a high surface area when it comes to their flow. The number of ideas coming into and out of the brains of faculty over time — our “idea flux”1 — seems higher. This doesn’t make us smarter than other knowledge workers (we’re not) but ideas have a currency with faculty that you don’t find elsewhere to the same degree.

The abundance of fascinating ideas is one of the reasons we were drawn to this field. However, this also means we're constantly exposed to more ideas than we can pursue, which can be overwhelming. We can’t possibly pursue all the ideas we experience, but not pursuing them seems wasteful. So what do you do with an idea that captures your attention but you don’t have the time, energy, or life situation to follow it?

Today, let's explore some common pitfalls in handling intriguing ideas and then delve into a powerful tool: the Someday/Maybe list.

How not to handle an intriguing idea

If an idea comes to you, there are three ways to handle it that you should avoid.

Ignore it. What I really mean here is “fail to capture it”. Capturing, you’ll remember, is the act of taking something that gets your attention and then getting it out of your head and into a trusted system. Failing to do this typically does not involve consciously turning your attention elsewhere. Instead, it looks like having the idea and then keeping it in your head – telling yourself that you’ll remember it later when needed. In my experience this almost never works: You think you’ll remember it because every good idea seems singularly memorable at the time. But you won’t. Psychologists are generally in agreement that short term memory can hold a maximum of 7 ± 2 chunks of information at any given time. That idea is one of those chunks, and if you have a high idea flux then that chunk will be long gone in a matter of minutes or less. Trying to remember an idea without capturing it is basically ignoring it.

Capture it, and then ignore it. You can also capture the idea into a system (Google Keep, a task manager, a notebook) but then not be in the habit of Clarifying what you capture, so the captured idea just sits there in the notebook or file until you’re no longer aware of it. I have dozens of notebooks filled ¼ of the way through with ideas that went there to die.

Put it on a to-do list. This one may seem odd. Shouldn’t we want to put intriguing ideas on a list of things to do? Isn’t this the way to turn them into something concrete and real? Not necessarily! The main pitfall of taking good ideas directly to a to-do list is that we may just not be in a place right now to “do” them. We may be oversubscribed with our current commitments; we may need tools or training that we don’t have yet and won’t have for some time; we may just have a sense that the timing is not right. If we don’t process ideas through the lens of what we’re truly capable of doing in the moment, the to-do list becomes just another graveyard for good ideas. Except, even worse, we can get so overwhelmed by the number of things to do that none of them get done.

There are other problems with putting ideas directly onto a to-do list. For example, an idea may not be a single action — it might be a question you have, whose answer involves a number of different actionable steps that have to be done separately and in a particular order. In that case, the idea is not a “to do list” item but a project, which is dealt with differently than single actions.

All three of these approaches are to be avoided for the same reason: They don’t honor the idea that you had. One way or another, the idea gets lost, whether in the recesses of memory or in a half-filled notebook that sits on the shelf or an overstuffed to-do list that never gets touched. And there is something tragic about losing an idea, as you know if you’ve ever had to spend time trying to remember one that you lost. For an academic, it can be like losing a part of yourself.

The Someday/Maybe List

So, how should you handle a good idea in a way that honors it, whether or not you’re able to act on it right now? The Getting Things Done framework gives us a particular tool for this: The Someday/Maybe list.

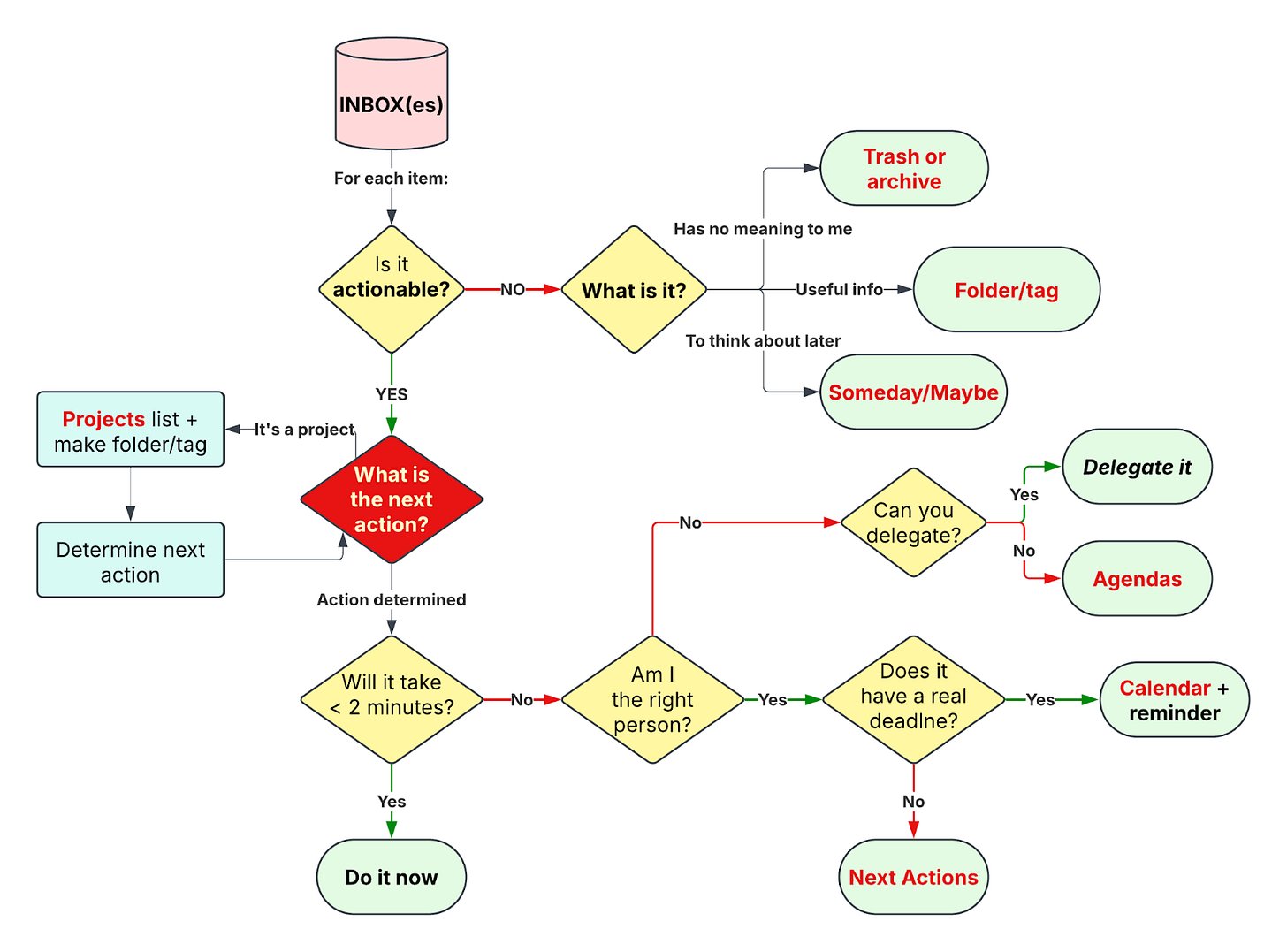

In the GTD framework, once we’ve captured something that gets our attention, we clarify it: We interrogate the item to figure out what it means to us. The Clarify process is often depicted as a flowchart, which I’ve adapted below to fit the needs of academics specifically:

The first thing you ask of a captured item is: Is it actionable? Does it require some specific action or group of actions? The answer is not always “Yes”. The item might simply be irrelevant (e.g. spam email). It might be relevant but just information (e.g. a report from a committee you’re on that contains no action items). Or, it might be interesting and relevant for you, and there is some action involved, but you can’t act on it now or choose not to act on it now — but you would like to come back to it someday, maybe.

The Someday/Maybe list is the current list of all the captured items that fall into that last category. And it is where (I would argue) the majority of the intriguing ideas that we have should live.

For college faculty, this list may contain things like:

Books to read

Articles to write

Research projects or questions to pursue

Courses to develop

Conferences to attend

Professional development activities to pursue

It can also contain tasks that you would like to do that are minor in size or scope, but you don’t want to commit to doing them now — but someday, maybe. And if you choose, you can include personal items on this list, like restaurants to try or places to vacation.

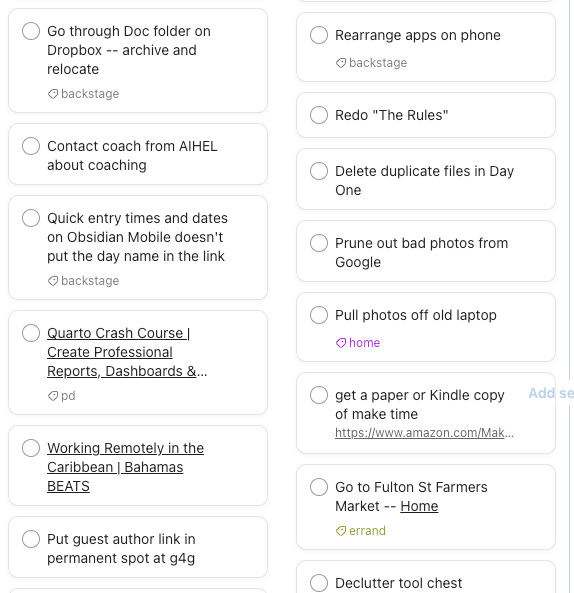

Here is a look at a portion of my own Someday/Maybe list, which I have arranged so that professional items and personal items are in different columns:

Some of these are big aspirational items (like working remotely from the Caribbean!), while others are sort of trivial everyday items that I need to do at some point (decluttering my tool chest in the garage) but I have no time frame for when I’ll do it. Others are in between. But all of them are ideas I once had, but I cannot or choose not to do them right now or within the next year. Rather than throw them out, or pretend that I’ll remember them, they live here.

I think the Someday/Maybe list is the most important list that an academic can have, even moreso than the Next Actions list which is the list we operate from when we do our work. It’s because the Someday/Maybe list is a holding area for all the ideas that inspire you, or have the potential to inspire, and you want to keep them around so you don’t forget you had them — but you have made the honest and realistic judgment that now is not the time for them. It’s a place of hope and excitement, where you can return when you feel burned out, and you can remind yourself of the cool ideas you had that can still become reality.

And on the note of “becoming reality”, the Someday/Maybe list should be reviewed regularly. Part of the weekly review process is to go through the Someday/Maybe list and “promote” anything that is on there that you now have decided you’re going to commit to doing, to the Next Actions list.Likewise, some items on the Next Actions list might be relegated to the Someday/Maybe list if they are no longer near-term commitments that you wish to make. Anything on the Someday/Maybe list can, and many times does, become a “live” project or action when the timing is right. Nothing is off the table forever.

Using the Someday/Maybe list in everyday practice

I wanted to say a little more about how the dynamic that I just mentioned — the back-and-forth between the Someday/Maybe list and the Next Actions list — works, because it was a key insight I had last summer as I was auditing my workflows.

The Next Actions list is the current list of all tasks that have been captured that are actionable, are single actions (not “projects”), would take longer than 2 minutes to complete, are best done by you and not someone else, and do not have a strict deadline. As I mentioned, this is the list we operate out of when we do our work2 and so it gets most of our attention.

It can also become a dumping ground for “stuff that seems worth doing”, without giving much thought to how committed we are to those things. I used to take the approach that anything that I wanted to get done should go on the Next Actions list, and the Someday/Maybe list was reserved for high-level aspirational items like “get a second Masters degree”. So in practice, about 80% of my tasks were on the Next Actions list and 20% were on Someday/Maybe. This equated into hundreds of items on the Next Actions list.

At the end of the previous academic year, I found myself in a state of very low motivation and my professional purpose and mission seemed very unclear. I took the summer to try to understand why. It didn’t take long to realize that the sheer number of Next Actions I had queued up was shutting me down — the classic fight-or-flight response that everybody with a too-large to-do list experiences. It’s simply demoralizing and demotivating to have a bunch of commitments that you’ve made that you then realize you cannot fulfill.

And that’s the key insight: Every next action is a commitment to completing the action. It occurred to me then that I need to add one more question to the chain in the Clarify process: Is this item something that I am committed to completing within the next six months? If I cannot honestly commit to completing the action on that time frame, it goes into Someday/Maybe instead.

After I had that realization, I applied that question retroactively to all the items that at the time were in my Next Actions list. In particular, any Next Action that had been added longer than six months prior, I either deleted or moved to Someday/Maybe — those were items that by definition I had not committed to doing, so there was no point pretending otherwise. In one afternoon I flipped the percentages on those lists: 80% of actions were now in Someday/Maybe and 20% were on the Next Actions lists. This got my Next Actions list down to about 60 items, and suddenly I found that I could breathe again.

I think this ratio, about 4:1 between Someday/Maybe and Next Actions, is the right one. That is, for every five ideas you have that are worth keeping around, you should commit to doing one of them relatively soon, and the others go on a list where they can be preserved and then promoted later when the time is right. Being very picky about the tasks you commit yourself to, having a very small number of tasks to which you are truly committed, and then actually getting those done, seems like the antidote to overwhelm and burnout. You become the kind of person who doesn’t let things “slip through the cracks” because there are no cracks.

And you still get to keep all those intriguing ideas around, ready to pounce on them when the time is right. What’s better than that?

Now You Do It

Grab a notebook or sheet of paper, or open up a new Google Doc, to serve as your Someday/Maybe list.

Go through your to-do list or Next Actions list, Clarify everything in it, then move roughly 80% of it into this new Someday/Maybe list.

Commit for the next few days to capture items that get your attention, then Clarify them in a single weekly review this weekend, and be honest about whether an item belongs in Next Actions or Someday/Maybe. Remember you can always promote a Someday/Maybe item to Next Actions later.

Etc.

A lot of people use Google Docs but aren’t aware of the relatively new tabs feature they have. In my view this supercharges Google Docs and makes them a viable GTD platform. You can, for example, have a single Google Doc with a tab for your Inbox, a tab for Someday/Maybe, an additional tab for each context, and so on.

Some instances of Google Workspaces have a very tight integration of Google Tasks with Google Docs that seems promising. You can create tasks in a Google Doc by typing @task, then give the name and assignee of the task, and then that task shows up in the assignee’s Google Task list with a link back to the document. Pretty cool.

Music: A bass video, unsurprisingly, but a different kind this time — Jing Yun Wang plays a gorgeous rendition of Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata on the double bass. As a former double bass player, I am in awe of the musicality here not to mention the sheer physical skill it takes to play this beast of an instrument.

I thought I had just coined this term but it turns out James Quiambao came up with it first.

Technically, GTD practice is to section this list by contexts — the tools, locations, or situations that are necessary to complete an action — and then operate out of the single context that you are in at the moment.