How and why I use ToDoist

A personal operating system for being intentional

This week I’m concluding a two-part series on the software tools I use to implement a lot of the ideas you read about on this blog. Last time, I wrote about Obsidian and how I use it to curate information and discover connections between ideas. This week, I’m focusing on the one app that does the most for me: ToDoist.

Before we get started, let me remind everyone: Being intentional about your life and work is not, and must not be, about apps and gadgets. It’s about behavior modification and building good habits. Note that this is only a two-part series because Obsidian and ToDoist are the only two specific tools I rely on. Everything else (calendar apps, text editors, etc.) are replaceable and interchangeable and this is on purpose. Even Obsidian and ToDoist can be replaced if needed1. What I do and what I use won’t work for everyone, but I do recommend not getting married to particular apps.

What is ToDoist?

At the most general level, ToDoist is software that manages lists. You could use it, for example, to keep track of your grocery list or a list of books you want to read. This is pretty useful in itself. But, as its name suggests, ToDoist is designed to manage specific kinds of lists, namely task lists.

I could have said “to do lists”, which is a more familiar term and rhymes with the name of the app. But the concept of the “to-do list” has some fundamental flaws. I may have more to say about that later. Suffice to say that the best way to understand why ToDoist is so useful is to think of it as task management software and not just something for holding to-do lists.

ToDoist is available as an app on all major desktop and mobile operating systems and through a web browser interface. The screenshots I’ll include here are from the macOS app2. Tasks entered into the app automatically sync across all devices (and does so very quickly). The full version of ToDoist costs $48 per year and that basically pays for syncing3.

When you open the app, you have nice clean interface that looks like this:

The top cluster of shortcuts on the left has a button to add tasks, another to do a search, an inbox for incoming tasks that you have captured but not yet clarified, and icons to show tasks due today and due soon, and an icon that is a shortcut to “Filters and Labels” which I’ll explain in a moment.

Below that is a list of projects. It will become very important later to understand that, from ToDoist’s point of view, a project is just a folder that holds groups of tasks. This need not correspond to how we think of “Projects” in the Getting Things Done framework, where they are desired outcomes that require more than one action step and that you intend to complete within 12 months.

Then there is an area for tasks and projects that are shared. This is useful if you’re part of a team collaborating on stuff, but I don’t use that functionality myself.

In the main interface you see the tasks themselves. Each one is just a short actionable statement, with some extra info added: a date or time, for example. You can also add comments and file attachments to each task. And if you look to the far right, you’ll see that each task has an indicator (using the hashtag symbol) of which project it belongs to. Some tasks also have labels (for example the one that says “Plan user research sessions”) that are tags that just add metadata. Some, like the one about yoga, have a little arrow circle indicating that it is a recurring task.

The circle next to a task is a checkbox, and when you complete the task, you click in the circle and it makes a satisfying little “pop” sound. Some of those circles have colors, that indicate priority levels. Plain white ones are “priority 4”, blue ones are “priority 3”, there is a red one at the bottom that is “priority 1”, and not shown is an orange circle indicating “priority 2”. There is no inherent definition of what those priority levels mean; that’s left for the user to define.

Entering information into ToDoist is simple and can be done in multiple ways. You can go to the inbox and just start entering things. Or, you can use a keyboard shortcut (on macOS or Windows) to quick-enter tasks from anywhere. Or, if you are in your email and you have a message that constitutes an actionable item, the ToDoist inbox has its own email address and you can forward the email directly into it, and it gets turned into a task with the text of the email added as an attachment. A recent addition to the app invokes AI to scan your email and create a task description that sums up exactly what the actionable item is4. When entering tasks into the system, there are keyboard shortcuts that will let you add labels, priorities, and dates/times to the task.

Filters and searches

Most academics, if they were to fully brain-dump their projects and tasks into this app, will end up with hundreds of entries5. With that much in the system, it’s hard to remember what you put into it and to find the right task or subset of tasks to do in any given moment where you have time and headspace to work. That’s where searching and filtering comes in.

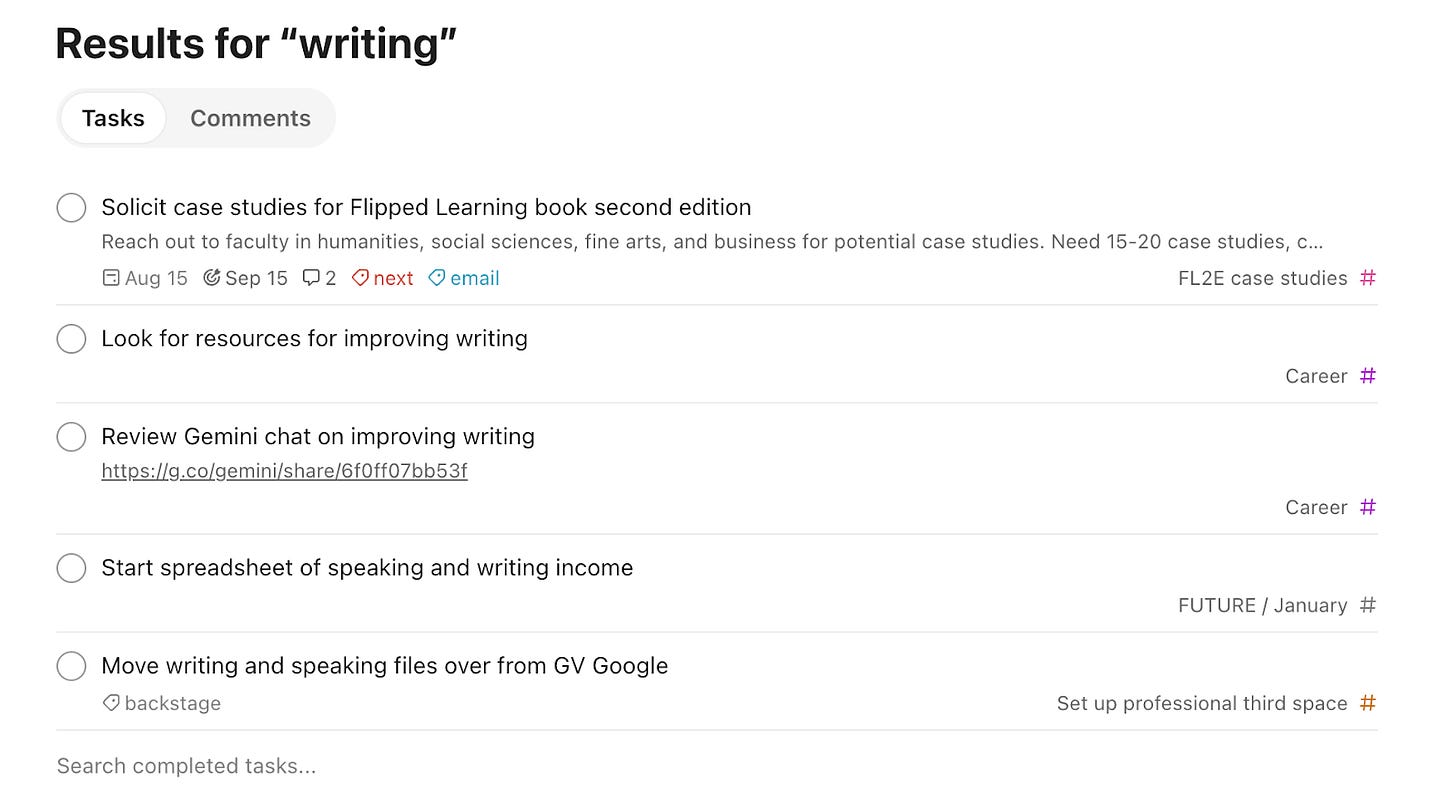

ToDoist has a powerful and flexible search engine that allows for considerable nuance. Let’s say for example that I am looking for all tasks that have to do with writing. If I click on the search button — or use the keyboard shortcut, / – and enter writing, I get a list:

If I realize later that some of these writing items use “write” instead of “writing”, I can do a Boolean search where one or the other keyword is used, using the syntax (search: write) | (search: writing).

Full documentation on search syntax is here (and yes, I have to refer back to that page often for the details).

You can also do search queries using labels, project names, dates, and more. Basically any metadata you choose to add to a task can be leveraged into a search query. Indeed that’s the main reason you would add that data in the first place.

Since doing these searches is really useful in everyday practice (see below), you can save them, as what are called filters. I have a filter set up, for instance, that brings up all my next actions that are not related to course prep or grading and which belong to active projects, for those times when I need to get work done but want to ignore (for the moment!) all the teaching-related stuff6. Filters can be “favorited” and they’ll then show up in the left sidebar for easy access.

How I use ToDoist

Now that you know what ToDoist is, what it looks like, and a bit of how it functions, let’s talk about how I make it work for my own daily practice. Different people use the app differently and you should never take my own practice as normative, or even fully functional. This is the result of 10+ years of daily use and evolution and there are a lot of idiosynracies.

In the GTD process, ToDoist fits into these parts of the flowchart:

In other words I use ToDoist for anything that I capture that either is actionable now, best done by me, cannot be done in 2 minutes or less, and does not have a hard deadline; or things that are not actionable now but might be of interest later. This is a very large number of things.

Let’s begin with “next actions”. Unfortunately this gets a little complicated.

In GTD there are really two kinds of next actions: Those that come from projects and those that don’t. Every GTD project must have a “next action” defined for it — the next physical step that you can take that will move the project forward to completion. But not every “next action” belongs to a project. For example, “Pick up prescription from the drug store” is a next action, but it does not belong to some larger outcome — it’s just a one-off thing I need to do. “Write draft of Todoist post” on the other hand, is a next action but it belongs to the GTD project “Publish article about Todoist”.

Why this matters here is that ToDoist does not natively have a way of distinguishing between these two kinds of actions: In ToDoist, if a task is not in the inbox, then it has to belong to a project. This is a significant Organization problem, because when processing items captured into the ToDoist inbox, they have to go somewhere other than the inbox, and if they don’t belong to a project then where do you put them?

To solve this problem, remember that what ToDoist calls a “project” is really just a folder. These “projects” do not have to be real projects in the GTD sense. And, since “projects” in ToDoist are just folders, you can also have “subprojects” which are just subfolders inside a larger “project”. Ordinarily creating subprojects off of a main project would not be good GTD practice7 but here they going to be quite useful.

So my approach to managing next actions is:

At the top level of “My Projects” in the sidebar, I created a “project” (= folder) called NEXT ACTIONS. This is where all one-off, non-project-related next actions go.

Below that, is a “project” ( = folder) titled PROJECTS. Inside this “project” (= folder) is a “subproject” (= subfolder) for each of my actual projects.

And inside each “subproject” (= subfolder) are the tasks related to that actual GTD project.

It makes a lot more sense visually:

Inside each of the actual GTD projects here, are the tasks related to the project. At my weekly review I make sure each actual project has a “next action”, and the way I distinguish these is by adding the label next to the project’s next action:

This means that every “next action” in my system is one of two things: An item in the NEXT ACTIONS “project” if it’s a one-off task, or an item with the next label if it belongs to a project.

When it’s time to work, I want to have a list of all the next actions — both the one-offs and the project tasks — in a single place in front of me, so I can choose what to do. To create that list, I go back to the concept of a filter: namely the filter that searches (p:NEXT ACTIONS) | @next. Read this as, “All items that are in the NEXT ACTIONS “project” or which have the next label”.

This is not the only way to dial up tasks to work on. In GTD practice we use contexts that correspond to specific tools, locations, or other constraints that define what you can possibly do in the moment. For example, my campus context corresponds to any task that must be done while I am on my university’s physical campus; phone corresponds to tasks that can only be done by making voice calls; and so on. The idea is that these contexts are supposed to partition your life, so they are mutually exclusive and the union of them all covers all possible life situations8. So at any moment, you look at the context you are in, and only focus on the tasks in that context because it would be a waste of energy to do otherwise.

Contexts are easy to implement in ToDoist via labels. I have a label set up for all my major contexts: email, home, errand, phone, campus, and few more. I also have contexts set up for “zones” of work, for example music for music-related tasks or quick for tasks that don’t take a lot of time. (I used to have a brainless context when I was a sleep-deprived new dad, for tasks I could do if I were running on fumes.) When I’m in a particular context, I can just do a search on the label, which can be done the usual way or just by clicking on the label in the app. Labels can also be combined with other searches, for example (@next | p:NEXT ACTIONS) & @errands brings up all the tasks that are next actions and require that I am out and about running errands.

Some other elements of my setup worth mentioning:

I mentioned four priority levels you can add to each task. I use “priority 1” (red) for my MIT, “most important thing”, for each day which I set up in the morning. “Priority 2” (orange) is for tasks that I would like to get done that day (but there is not necessarily a deadline). “Priority 3” (blue) is for things I would like to get done that week. “Priority 4” is everything else. (You can search on priority levels too, so if I wanted to see all the writing tasks I wanted to finish this week, I’d search (p1 | p2 | p3) & @writing.

My Someday/Maybe list is set up as another “project” (folder) that lives at the top level of projects. I find it’s better to keep this list in ToDoist than in Obsidian, since Someday/Maybe and your next actions lists are constantly flowing into and out of each other. Each week there are Someday/Maybe items that get “promoted” to next actions and some next actions that get “relegated” to Someday/Maybe. This is easier to implement if both lists are in the same app.

There is currently no native way in ToDoist to create a task that has a start date in the future, as would be handled by a tickler file. So I have yet another “project” (folder) called FUTURE that holds these. A new-ish feature of ToDoist is the ability to add “sections” to projects, which are not subprojects but just containers for related tasks within a project; I have sections for each month and move future tasks into the FUTURE project and then into the month I intend to start them. Then review this area each week especially the first weekend of each month.

I have another “project” (folder) called PARKED that holds all actual projects (subfolders) that are on hold. Each week at the weekly review, I examine this folder and re-activate any project that’s back in business and move any newly-inactive project down into that folder. Most of my filters have search queries that exclude anything from the PARKED folder so that I’m not looking at tasks from inactive projects.

Who this tool is for and why you might use it

If all you want is to capture your “to-do list” items, store them in a trusted system, and have the ability to look at them when you want, then you do not need ToDoist or any other app. You could very easily do this with a paper notebook, or Google Docs, or just a stack of index cards and skip all the complicated stuff I just discussed.

The problem with that approach, is that at some point you have to engage with the tasks that you have put into your list. In a simpler life, a basic to-do list in a paper notebook would be perfectly adequate for daily work. But for modern academics, the list of things that we could do, and which we have committed to doing, is so long and diverse that just having these in a list is instantly overwhelming. In fact I think a lot of what we call “burnout” stems from the paralysis we naturally experience when confronted with a list of commitments we’ve made that is so large we cannot possibly do it in any reasonable time frame.

So the value proposition of ToDoist, and the reason a person might want to use it, is that it is more than just a handy way to capture and organize tasks: It provides the ability to easily slice and dice your massive master task list into much smaller context-appropriate task lists, which we can then actually think about without our brains freezing up. Rather than just doing the most urgent, latest-and-loudest item on a to-do list — or the easiest one — ToDoist makes it easy to dial up a manageable menu of tasks we’ve committed to doing, that represents the right things to work on in the moment. We can then pick one of those things off the menu and engage with it, without the lingering FOMO/guilt feeling that there is something else that you ought to be working on instead. I cannot overstate how important this point is, for our own sanity and usefulness to others.

There are other apps out there that do what ToDoist does: OmniFocus, TickTick, Things, and a million others9. What makes ToDoist stand out for me, and why I keep coming back to it if I try out another tool, is:

ToDoist is cross-platform and has a web interface, and syncs across all devices quickly and error-free in my experience. Some competitors (like OmniFocus) work only on one OS and do not have an OS-agnostic web interface10.

The search and filter features which I have described at length. Other apps have these but ToDoist’s seems the simplest and most natural.

The price, which as I mentioned is $48 per year. There is no educational pricing but honestly, you probably don’t need it when the price is already this low. It is by far the best price-to-use ratio I have encountered in any software ever other than free stuff.

This post is ridiculously long, so I will end by saying that while ToDoist is a good choice for many people using GTD, it is only as good as your commitment to the habits of GTD, especially weekly reviews. No app or gadget is going to work for you if you don’t stay consistent with using it, and you must review your system, consistently and regularly to get the most out of it and keep it from becoming a hindrance. The app will not do the real work for you!

Recall I made a big deal last time about Obsidian being nothing more than a wrapper around a folder of Markdown files, so the files are still present and usable even if Obsidian goes away.

There are some differences between this and the interface for the mobile app that, frankly, can be annoying at times and I wish the ToDoist team would work on creating a more consistent UI across devices.

There is a free tier, but it’s quite limited at only 5 projects allowed. The cost of the full version is, to me, incredibly low and the company deserves kudos for keeping costs down — the cost of the full version 10 years ago when I started using the app was $36 per year.

This AI integration is quite astonishingly accurate and I don’t think I fully appreciate how incredibly helpful it is. In a sense the AI is looking at the email and figuring out what the next action is supposed to be – which is the really hard work in GTD.

It is so easy to dump stuff into ToDoist, in fact, that you have to be careful to think critically about an item, just for a moment, to decide if it’s truly worth capturing, otherwise you will end up over-capturing and having all these things in the system that seemed to matter in the moment but later on are just dead weight. This can be remedied by good reflection practices e.g. a Weekly Review but it’s an unintended gotcha of the app being so good at what it does.

The query, if you must know, is: (@next | (#NEXT ACTIONS)) & (!#Grading) & (!#Course Prep) & (!(#FUTURE)) & !(#SOMEDAY/MAYBE) & !(##PARKED). More on some of what this means in a minute.

Subprojects are not a well-defined GTD concept. If you have a project that seems to require a subproject, you just make the subproject a project in its own right. If it comes to that, perhaps the “project” was more of an area of focus than an actual project.

In practice, life is a lot messier than this, and many GTD people today view contexts as a relic of the 90’s when David Allen invented the framework and life/work was a little simpler. I still use contexts as reasonable approximations of a partition.

I have a long history with these tools. When I first discovered GTD, I started with one of the OG task management tools, Kinkless GTD, which at the time (mid 00’s) was just a bunch of Applescripts acting on OmniOutliner. That system later became OmniFocus, which I used until I stepped outside the Mac ecosystem. I then bounced around using Nozbe, ToDoist, todo.txt, TickTick, Trello, a paper notebook using bullet journaling, and probably others I’ve forgotten about. In the end I kept coming back to ToDoist as the best combination of simplicity, power, cross-platform availability, and price. Although I have to say, Kinkless GTD was awesome and I miss it.

OmniFocus does have a web “companion” but it is an add-on subscription at $5 per month, is not a standalone product, and does not work fully on a mobile device.

Brilliant post. I’ve been using ToDoist, as a GTD tool, since 2018 and it has been a lifesaver. Your technical set up is very similar to mine, although I’m going to adopt your @next tags - brilliant tweak.

The gold of your post is that you’ve expressed why having a system helps prevent work stress and burnout. I am an academic physician and academic and clinical leader so the chaos of demands on my time is insane. ToDoist set up thoughtful and used with systematic discipline (which is not time consuming) has been the mechanism by which I’ve stayed a productive and reliable academic. Anyone reading the blog post - he’s right! Try it!

Thank you

I've always had a hard time using both a calendar and Todoist. Having my calendar linked on Todoist doesn't have the same satisfaction or sense of achievement as checking a box, but I can't seem to completely transition over to Todoist for recurring tasks/collaborative meetings for three reasons:

1. Todoist doesn't have a very robust recurring task management system (e.g., MWF in a single week), forcing me to create multiple redundant tasks that say effectively the same thing

2. It does not give insight into the duration of an event

3. I end up having to use the calendar anyway to invite participants, effectively doubling the overhead

I wonder if you have dealt with these issues, and, if so, how you've resolved them.