Have you ever been ghosted? This happens when you send a message to someone – email, text, whatever – and you expect a reply, but time keeps passing and you never get one. Actually, this is a bad question, because of course you have been ghosted. If you’re like me, the question isn’t whether it’s happened to you, but how many times has it happened so far this week. And to be fair, we can at times be the person doing the ghosting.

Now that we’ve had three big-picture articles in a row about the axioms on which an intentional academic life is based, let’s think about what those look like on the day-to-day level. And there’s nothing more day-to-day than email and other forms of messaging. It’s safe to say that not many academics approach email intentionally; it’s like an unwelcome visitor, constantly present with you, grabbing at what’s left of your attention.

The most basic form of “intentional email”, is not ghosting people but rather, if you must use email at all, to be fully present with it and the people emailing you. Ghosting happens so much to me that I have developed some personal rules about it. Details are below, but the basic guidelines are:

Ghosting is bad and you shouldn’t do it if you can help it.

But, ghosting is not always unjustified, and sometimes it’s OK (even though it’s still kind of bad).

Instead of ghosting, learn when to reply and when not to reply and then make replies as efficient as possible.

Ghosting is bad

Some of the worst instances of ghosting I have encountered are on Facebook. I know, Facebook. But for better or worse, and for whatever reason, Facebook is the de facto communications platform for all musicians in my area. And musicians, being notoriously squirrelly, are prone to ghosting.

For instance: In June 2024, someone from a blues band in Lansing posted that they were looking for bassists, preferably over 50 years old. Great!, I thought, so I replied to the post asking about rehearsal and gig schedules. A couple of days passed. Then a week. Then a month. Then three months. The six months. Finally, this week, I got a reply apologizing for taking so long and asking me to please direct-message (DM) him. I did so. A couple of days passed… and no reply. Here we go again, I thought. Then on day 3, the guy re-posted the same request from last June and asked people to – wait for it – DM him if interested. At that point I just gave up.

Ghosting is bad and we should avoid it if we can help it. To the person you are ghosting, it presents itself as a deliberate refusal to engage. Note well, this may not be the reality1, but to the person being ghosted there is no reason to believe otherwise. To them, fairly or otherwise, it simply appears that they’re not worth the effort.

In an academic context, this appearance of a deliberate refusal to engage can have serious consequences, especially if it involves students. Part of the social contract we make with students is that, as their instructor, if they have a question that needs answering then we will make a good-faith attempt at answering it on a reasonable time scale. That time scale is not necessarily immediate, but it’s not measured in weeks or months either. The same is true for service and research commitments, all of which involve other people putting their trust in each other.

Even when it involves people with whom we have no relationship yet, like my friend in the blues band, it’s bad because it’s disrespectful and shuts down any potential relationship. If that person in the blues band had replied within a few days, even just to say that they weren’t interested in me, I would be disappointed but I would at least know where I stand and can close that open loop in my mind. Instead, I was left hanging, again as if I were not worth even the effort of typing out one sentence. Who wants to be in a band with someone who doesn’t respect them?

So ghosting is in some ways the opposite of the intentional approach to academia that we want, where we value people even as we wish to be valued and honor other people’s time just like we want ours to be honored. It’s about as unprofessional as you can get.

Except when it isn’t. Because I think that sometimes, ghosting is OK.

Sometimes ghosting is OK

Ghosting is bad and we should avoid it when we can. But sometimes it’s unavoidable, and sometimes, it’s not exactly justified but can be forgiven if we do it.

I can think of four different situations where ghosting someone is OK:

When the message is abusive. If you get an email, direct message, or text message that is hateful or abusive, just block and report the person but do not reply. This is a behavior that should be extinguished, not reinforced.

When there is an external rule that prevents you from replying. I am thinking of Human Resources policies here. For example, if your department is hiring a faculty member and you are not the chair of the search committee, sometimes a candidate might email you personally and ask for something (inside information, to put in a good word for them, etc.). Policies on this situation vary, but the HR department may have a rule against giving special treatment to a particular candidate, which a reply to that person’s email could be construed to be. You can ask HR about it and leave the message unreplied in the meantime; but the legally correct response might be ghosting. (Or, forwarding the request to the chair, or something else in which you personally do not reply.)2

When the original email is a question you already answered (and the answer is accessible to the sender, like a course announcement). Here it gets a little tricky. If I post a course announcement that says “We are rescheduling the first exam to Monday” and this announcement gets sent out to all my students, and then I get a message from a student asking when the first exam is, I probably would not actually ghost the student but if I did, I wouldn’t feel bad about it. After all, the announcement is sitting there in the very program that the student is using to email me. Replying might actually be a net negative, because it reinforces the belief that you don’t have to read course announcements, you can just always shoot the prof an email instead.3

The original email was unsolicited and has no meaning to you. By “has no meaning to you”, I am referring to the Clarify process which is part of the Getting Things Done workflow. In that process, if an item that has been captured is not actionable, and it is neither useful reference information that you need to file away nor something you want to think about in the future but not right now, then it “has no meaning to you”. The appropriate action for such things is to delete them or archive them. If it’s from a person you know, then you might give a quick reply before doing so (or not, it’s your call). But if it’s from a person you don’t know, then I would say don’t bother, and there’s no harm in ghosting the person.

I’m not saying that we should ghost people in all of these situations, because ghosting is always at least kind of bad. I’m merely saying that if you did ghost here, you’d have a reasonable excuse. But we should still avoid it if it makes sense to do so, especially because of the next section.

Simple replies are easy

This is not exactly the rule I said above, but let me explain: A crucial fact about intentionally managing email is realizing that not everything needs a reply, and the replies you do give can be easily made very simple.

Sometimes I will get messages that are not actionable: The email has the agenda for a meeting, or a message from a student telling me they won’t be in class today, etc. All useful and meaningful — but not actionable, and in the Clarify process they usually end up as info that gets filed away. So I do that. But then, I get an email asking if I got the previous email. For reasons unknown to me, this induces Hulk-like levels of anger in my brain. I am certain this happens to you as well, hopefully without turning into a green rage monster.

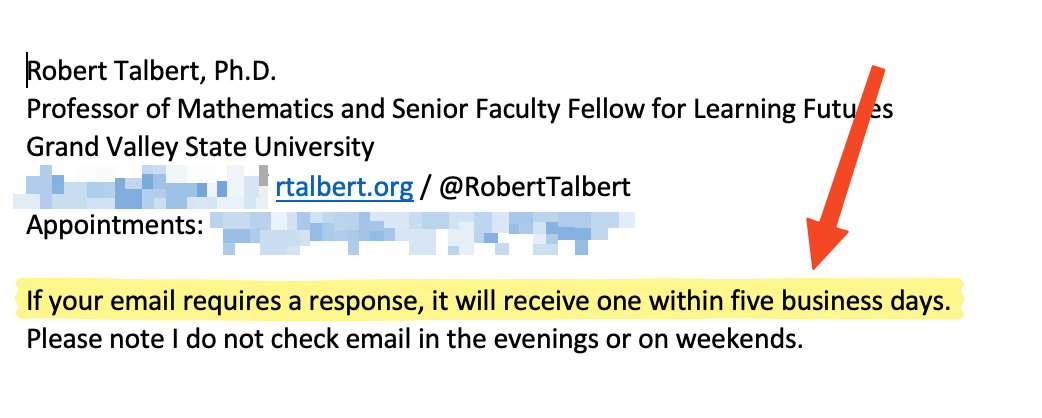

I would like all of us to normalize the behavior of not sending replies to email unless it’s obvious that the sender wants one, whether through an explicit request or making it clear from context4. I have even started including the following line in my email signature:

…which sends the message that if you don’t make it clear that you need a reply then don’t expect one. I don’t mean to be a jerk here; it’s just that, why would I reply to an email that doesn’t need a reply? It’s a waste of 2 minutes that I could spend actually doing something useful.

If this is a bridge too far for you, then there are simple reply strategies that you can use that do not involve spending 120+ seconds of your life typing out an email that doesn’t need to be written:

Emoji reactions. Outlook and Gmail5 now feature emoji reactions to emails, similar to what you see on social media. Instead of replying to a person “Thanks for the email” you can just click this button and it will ping the sender, using a heart or thumbs-up or something else, that the message was received. In my view, the emoji response button is the single best innovation in email in the last 5-6 years (followed closely by schedule send).

Canned responses. If you must use text, you can use a text snippet program like TextExpander or the built-in snippet feature in macOS if you are a Mac user to pre-write common text blurbs and then insert them into an email with a couple of keystrokes. For example I have this snippet in TextExpander to send to solicitors who I have previously ghosted but who keep bugging me6:

Out of office responders. You can use your email’s out-of-office auto-response feature for anything, not just literally being out of the office. For example, if I am actually in the office but doing heads-down focus work, I’ll set one up saying so and then leave it on for the day, and shut it off at the end of the day. This way you’re not ghosting anyone, but also not putting attention on their emails (until it’s the right time to do so).

But sometimes you have emails that do need a reply. What then? I recommend turning the reply into a two-minute action, which you therefore can and should do right away if possible. You can do this in a few ways:

Set a 150-word limit and keep the reply under that limit. That is about twice the length of the opening paragraph of this article. This should be plenty of room to make your point, within two minutes. If it isn’t, don’t wordsmith: Pick up the phone or walk down the hall and just talk to the person. Or do the next thing:

If you can’t do the above, then send this reply instead: Thanks for your email. I’m not able to reply in full right now, but I will do so soon once I have the time. I just wanted you to know for now that I got your message and will get back to you. You can turn this into a snippet and use it that way. Then, put “Reply to Person X” on your Next Actions list and get to it as soon as you can.

Long story short, there are cheap and quick ways to avoid both ghosting and getting embroiled in lengthy email replies and we should use all available tools to do so.

Now you do it

Here’s your homework for the next couple of weeks:

Look at the ten emails currently at the top of your inbox. (If you have fewer than 10, you can skip this homework.) Are there any that contain no actionable information — nothing that suggests you need to “do” something? Of those, are there any that don’t contain any reference information you might need later, and don’t represent something you want to think about later? If there are any that do all three: Delete them and don’t worry about ghosting.

Of the ones left over that you didn’t just delete, are there any that need a reply? Then go ahead and reply to each one, now, using less than two minutes each. (Remember there are a maximum of 10 things you are looking at, at this point, so this is at most a 20-minute job, and it will greatly ease your conscience.)

Extra credit: Keep going through the rest of your inbox.

Etc.

Another tool I did not mention is the entire class of task management apps that allow you to forward emails wholesale into the app and turn them into Next Actions. ToDoist is the one I use, but many others do. When there’s an email that is actionable but still doesn’t need a reply, I forward it into ToDoist and then process it later. (Rather than using my inbox as a to-do list which is a terrible idea.)

I’ve mentioned the so-called “two minute rule” here a couple of times. This says, if something you captured is a task that can be completed in two minutes or less, don’t “organize” it, just go ahead and do it right then. The problem with the two-minute rule is that humans are terrible at estimating how much time something takes. To mitigate this, my go-to tool is this simple analog timer. No apps, no batteries.

Music time: If you don’t know Snarky Puppy… I mean, just listen to this, especially the keyboard solo.

For example maybe the guy in the blues band was sick; or as is more likely the case, doesn’t really know how Facebook DM’s work.

Here’s another anecdote. Shortly after David Clark and I published our book on alternative grading, we got an “interview request” from a well-known right-wing-leaning website to talk to us about it. This website specializes in takedowns of happenings at universities that they deem to be “woke”, and our red flags went up. We forwarded the email to our publicity office, which conferred with our general counsel and send us back an immediate reply of do not engage. The university took over all communications with this website, and we were happy to hand over the reins.

In practice, I have a text snippet (see later in the article) that says basically, Thanks for your email, you can find your answer in the announcements or on the course calendar. So not “ghosting” but also not putting a ton of attention on the request.

Explicit requests are way, way better than “making it clear from context”. If you want a reply, just say so.

This feature’s availability in Gmail seems to depend on your particular setup. For example it’s available in my personal Gmail, but not in the Google Workspace Gmail that my university administers. At least not today.

I like snippets because as you can see in the title of that snippet, they allow me to write a nice, professional response once and then be irritated and passive-aggressive all other times.

I feel like the problem of ghosting begins at an earlier juncture, which is to say:

1) Don't send some of the emails that are going to get ghosted

2) Send emails that are highly intentional about describing what kind of response you want and that dramatically minimize the thought and attention that have to go into composing that response.

3) Send emails that have a lot of things to express but that are not easy to answer to with a strongly embedded pre-emptive "no reply necessary, I just needed to say this" that is sincerely meant.

You get at some of this, but from the perspective of the person doing the ghosting, which in many cases isn't really fair, because many emails put people in the position of having to consider the etiquette of ghosting are emails shouldn't have been sent in the first place or that should have been composed with the possible replies more clearly in mind.